Embark on a fascinating journey into the world of fermentation with “How to Choose and Use the Right Starter Cultures.” This guide unlocks the secrets of transforming simple ingredients into delicious and nutritious foods, from tangy yogurt and crusty sourdough to vibrant kimchi. Discover how these microscopic marvels – bacteria, yeasts, and molds – work their magic, creating unique flavors, textures, and extending the shelf life of your culinary creations.

This comprehensive guide will equip you with the knowledge to select the perfect starter cultures for your desired creations, understanding their different forms, and mastering the art of activation and maintenance. You’ll learn how to troubleshoot common fermentation challenges and create a safe, thriving environment for your cultures to flourish, allowing you to explore the exciting possibilities of home fermentation with confidence.

Introduction to Starter Cultures

Starter cultures are the unsung heroes of many delicious foods. They are essentially carefully selected microorganisms – tiny living organisms like bacteria, yeasts, and molds – that are added to food to kickstart fermentation. This process transforms raw ingredients into flavorful, textured, and often more nutritious products. From the tangy bite of yogurt to the complex flavors of aged cheese, starter cultures are responsible for a wide range of culinary delights.

What Starter Cultures Are and Their Purpose

Starter cultures are specific strains of microorganisms chosen for their ability to perform desired changes in food. Their primary purpose is to initiate and control fermentation, a metabolic process where microorganisms convert carbohydrates (like sugars and starches) into other compounds. This transformation results in changes in flavor, texture, and preservation.

Different Types of Starter Cultures

There are various types of starter cultures, each containing different microorganisms. The choice of culture depends on the desired food product.

- Bacteria: These are the most common type of starter culture. They are used in a wide variety of foods.

- Lactic acid bacteria (LAB): These are the workhorses of fermentation, converting sugars into lactic acid. Examples include Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, and Bifidobacterium. They are used in yogurt, cheese, sauerkraut, kimchi, and sourdough bread.

The lactic acid they produce contributes to the characteristic tangy flavor and helps preserve the food by inhibiting the growth of spoilage organisms.

- Propionibacterium: This bacteria is used specifically in the production of Swiss-type cheeses. It produces propionic acid and carbon dioxide, which create the characteristic holes (eyes) and nutty flavor.

- Acetic acid bacteria: These bacteria, such as Acetobacter, are used in vinegar production. They convert ethanol (alcohol) into acetic acid (vinegar).

- Lactic acid bacteria (LAB): These are the workhorses of fermentation, converting sugars into lactic acid. Examples include Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, and Bifidobacterium. They are used in yogurt, cheese, sauerkraut, kimchi, and sourdough bread.

- Yeasts: These are single-celled fungi that play a crucial role in fermentation, particularly in bread, beer, and wine.

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Commonly known as baker’s yeast or brewer’s yeast, this yeast ferments sugars into carbon dioxide and ethanol. The carbon dioxide causes bread to rise, while in beer and wine, it contributes to the alcoholic content.

- Molds: These are also fungi, often used in the production of cheeses and certain cured meats.

- Penicillium: Various species of Penicillium are used in cheese production. For example, Penicillium roqueforti is used to create blue cheese, while Penicillium camemberti is used to make Camembert and Brie. The molds grow on the surface or within the cheese, contributing to flavor and texture.

- Aspergillus: Some species of Aspergillus are used in the fermentation of soy sauce and miso. They break down proteins and carbohydrates, contributing to the unique flavors of these products.

Benefits of Using Starter Cultures

Using starter cultures provides numerous benefits in food production, enhancing flavor, texture, and preservation.

- Flavor Development: Starter cultures produce a wide range of flavor compounds.

- Lactic acid bacteria produce lactic acid, which gives yogurt, cheese, and sauerkraut their characteristic tang.

- Yeasts contribute to the complex flavors in beer and wine, with different strains of yeast producing different flavor profiles.

- Molds in cheese produce enzymes that break down proteins and fats, creating complex flavors. For instance, the characteristic sharp flavor of blue cheese is a result of the action of the mold.

- Texture Modification: Starter cultures alter the texture of food.

- The carbon dioxide produced by yeast causes bread to rise, creating a light and airy texture.

- Lactic acid bacteria coagulate milk proteins, forming the solid structure of yogurt and cheese.

- Molds contribute to the creamy texture of certain cheeses.

- Preservation: Starter cultures contribute to food preservation.

- Lactic acid produced by LAB lowers the pH of the food, creating an acidic environment that inhibits the growth of spoilage bacteria.

- The fermentation process can also produce other antimicrobial compounds, such as bacteriocins, that help to extend shelf life.

- Alcohol produced by yeast in beer and wine acts as a preservative.

Identifying Your Needs

Choosing the right starter culture hinges on knowing what you want to create. Different fermented foods require specific cultures, each contributing unique flavors, textures, and preservation properties. Understanding this is the first step toward successful fermentation.To get started, let’s explore some popular fermented food categories and the cultures they rely on.

Fermented Food Categories and Required Cultures

The world of fermentation offers a diverse range of delicious and healthy foods. Each category relies on specific microorganisms to transform ingredients, resulting in distinctive flavors and textures.Here’s a table outlining some common fermented foods, the cultures they require, and the resulting characteristics:

| Food | Required Culture | Resulting Characteristics | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yogurt | Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus | Tangy flavor, creamy texture, thickened milk. | These bacteria work synergistically; L. bulgaricus produces flavor compounds, and S. thermophilus helps thicken the yogurt. |

| Cheese (Cheddar) | Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris and/or Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis | Firm texture, tangy to sharp flavor (depending on aging). | These cultures produce lactic acid, which coagulates the milk proteins and contributes to flavor development. Additional cultures, such as Propionibacterium freudenreichii (for Swiss cheese) and molds (for blue cheese), can be added for further flavor and texture development. |

| Sourdough Bread | Wild yeast (various strains of Saccharomyces) and lactic acid bacteria (LAB, such as Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis) | Sour flavor, airy crumb, chewy crust. | The yeast leavens the bread, while the LAB contributes the characteristic sour flavor and helps preserve the bread. |

| Kimchi | Leuconostoc mesenteroides (primarily) and other LAB | Sour, spicy flavor, crunchy texture. | These bacteria ferment the vegetables, producing lactic acid and other flavor compounds. The specific flavor profile depends on the vegetables and seasonings used. |

| Kefir | Kefir grains (a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeasts) | Tangy, slightly fizzy, creamy texture. | Kefir grains contain a diverse range of bacteria and yeasts that ferment milk, producing lactic acid, carbon dioxide, and alcohol. |

| Sauerkraut | Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Lactobacillus plantarum, and Lactobacillus brevis | Sour, salty flavor, crunchy texture. | These bacteria ferment the cabbage, producing lactic acid and preserving the vegetable. |

| Kombucha | SCOBY (Symbiotic Culture Of Bacteria and Yeast) | Tangy, slightly sweet, effervescent flavor. | The SCOBY consumes sugar and produces acetic acid, gluconic acid, and other compounds that contribute to the unique flavor. |

Understanding the specific cultures required for each food type is crucial for successful fermentation.

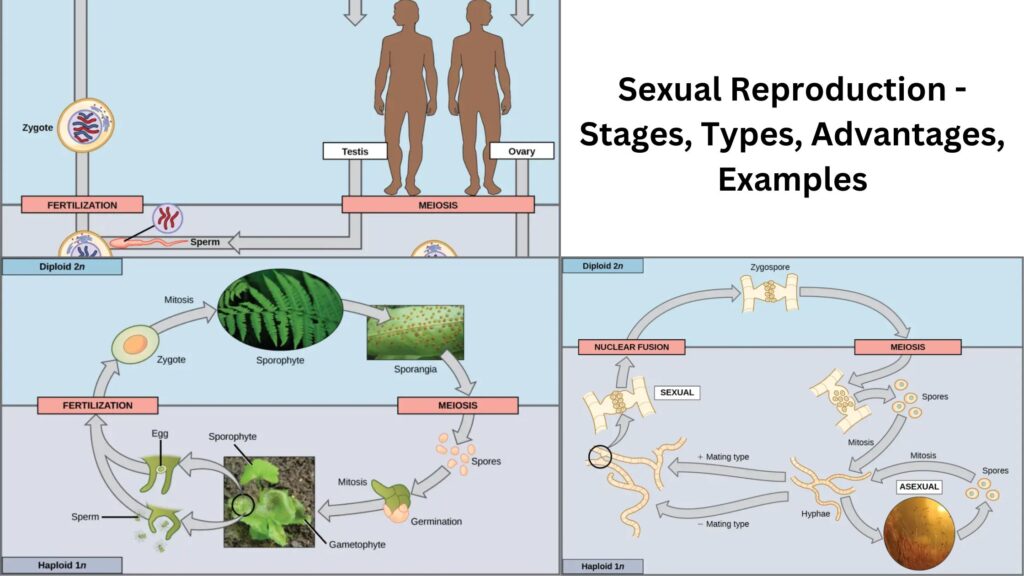

Understanding Culture Types

Starter cultures are composed of various microorganisms, each playing a crucial role in fermentation. These microorganisms, primarily bacteria, yeasts, and molds, work synergistically to transform raw ingredients into delicious and often nutritious foods. Understanding the specific roles of each type is key to successfully using starter cultures.

Bacteria in Fermentation

Bacteria are fundamental to many fermentation processes, converting sugars into various byproducts that contribute to flavor, texture, and preservation. Different types of bacteria are employed, each with its unique characteristics and metabolic pathways.Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB):

LAB are a diverse group of bacteria known for their ability to produce lactic acid from carbohydrates. This process, called lactic acid fermentation, is crucial for preserving food and developing characteristic flavors.

- Lactic acid production lowers the pH of the food, inhibiting the growth of spoilage organisms and pathogens.

- LAB contribute to the tangy, sour, and complex flavors found in many fermented foods.

- Examples of LAB used in fermentation include:

- Lactobacillus species: Used in yogurt, sauerkraut, and sourdough.

- Leuconostoc species: Used in kimchi and some types of cheese.

- Pediococcus species: Used in fermented sausages and pickles.

Acetic Acid Bacteria:

Acetic acid bacteria convert ethanol into acetic acid (vinegar). This process is essential for producing vinegar and contributes to the characteristic sourness and acidity of fermented products.

- Acetic acid acts as a preservative, preventing the growth of undesirable microorganisms.

- Acetic acid bacteria also contribute to the flavor profile of fermented foods, adding a sharp, acidic taste.

- Examples of acetic acid bacteria include:

- Acetobacter species: Primarily used in vinegar production.

- Gluconacetobacter species: Also used in vinegar production and the fermentation of kombucha.

Yeasts in Fermentation

Yeasts are single-celled fungi that play a significant role in fermentation, particularly in alcoholic beverages and bread making. They convert sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide, creating the characteristic characteristics of these foods.

- Yeasts are responsible for the production of alcohol in beer and wine.

- They also contribute to the rise of bread dough through the production of carbon dioxide.

- Different yeast strains offer diverse flavor profiles and fermentation characteristics.

- Examples of yeasts used in fermentation include:

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Commonly used in bread making and brewing. It is also known as brewer’s yeast and baker’s yeast.

- Saccharomyces bayanus: Used in winemaking, particularly for restarting stuck fermentations due to its tolerance of higher alcohol concentrations.

- Brettanomyces species: Often used in beer and wine fermentation, contributing complex flavors and aromas.

Molds in Food Production

Molds are multicellular fungi that are used in the production of several fermented foods, particularly in the ripening of cheese and the production of certain cured meats. Molds contribute to flavor, texture, and appearance of these foods.

- Molds often grow on the surface or throughout the interior of the food, creating unique textures and flavors.

- They produce enzymes that break down proteins and fats, contributing to the development of complex flavors and aromas.

- Examples of molds used in food production include:

- Penicillium roqueforti: Used in the production of blue cheeses like Roquefort and Stilton. This mold grows within the cheese, creating blue veins and a distinctive flavor.

- Penicillium camemberti: Used in the production of soft cheeses like Camembert and Brie. This mold grows on the surface of the cheese, creating a white rind and contributing to the creamy texture.

- Aspergillus oryzae: Used in the production of koji, a mold used in the fermentation of soy sauce, miso, and sake.

Culture Forms and Availability

Choosing the right starter culture form is crucial for successful fermentation. Different forms offer varying advantages and disadvantages in terms of convenience, shelf life, and ease of use. Understanding these differences allows you to select the best option for your specific needs and fermentation projects.

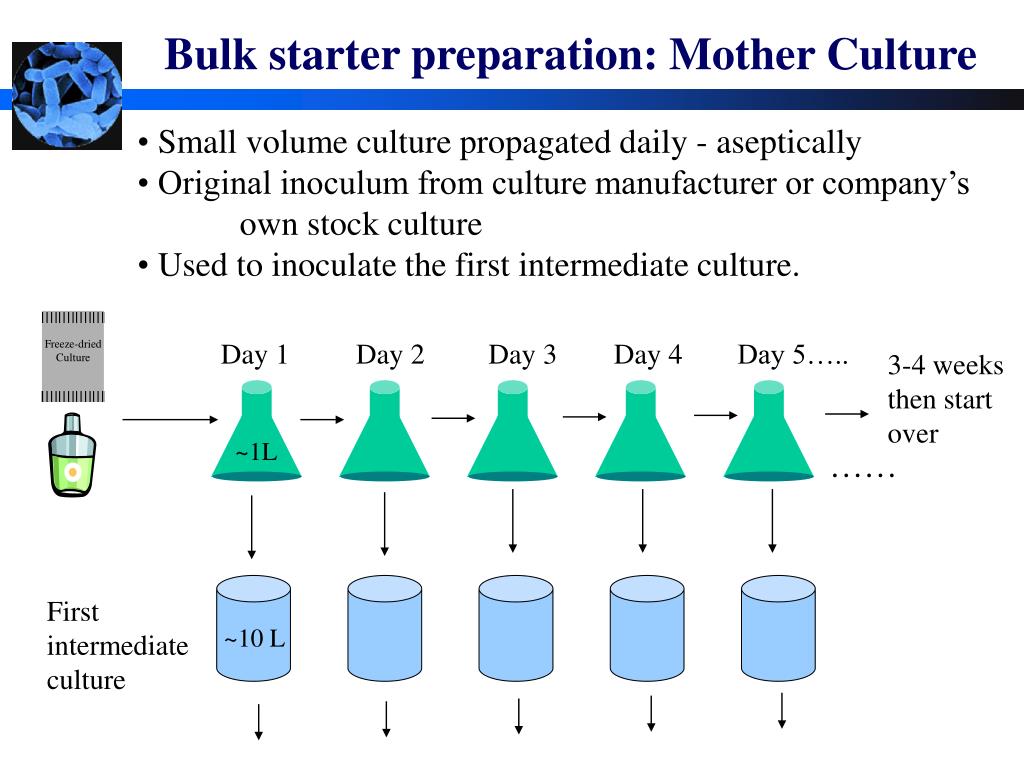

Freeze-Dried Cultures

Freeze-dried cultures are the most common form available. They offer a long shelf life and are relatively easy to store.Freeze-dried cultures are made by rapidly freezing the culture and then removing the water through a process called sublimation. This results in a powder or small granules that contain dormant microorganisms. To activate the culture, you simply rehydrate it with water or milk, depending on the specific culture and application.The advantages of freeze-dried cultures include:

- Long Shelf Life: Freeze-dried cultures can be stored for extended periods, often years, in a freezer. This makes them ideal for infrequent fermentation projects.

- Convenience: They are easy to measure and use.

- Portability: They are lightweight and easy to transport.

- Availability: Freeze-dried cultures are widely available from various suppliers.

The disadvantages of freeze-dried cultures include:

- Activation Time: They require a rehydration period, which can add time to the fermentation process.

- Sensitivity to Moisture: Once opened, they can absorb moisture from the air, potentially reducing their viability.

- Cost: Freeze-dried cultures can sometimes be more expensive than other forms.

Liquid Cultures

Liquid cultures are a ready-to-use form of starter culture. They contain active microorganisms suspended in a liquid medium.These cultures are often grown in a laboratory setting and packaged in sterile containers. They offer the advantage of immediate use, as there’s no need for rehydration. However, they typically have a shorter shelf life compared to freeze-dried cultures and require careful handling.The advantages of liquid cultures include:

- Ready to Use: They require no rehydration, saving time.

- Faster Start: Fermentation may begin more quickly due to the active state of the microorganisms.

The disadvantages of liquid cultures include:

- Short Shelf Life: They have a shorter shelf life compared to freeze-dried cultures, often requiring refrigeration and use within a few weeks or months.

- Storage Requirements: They typically require refrigeration, which can be a limitation.

- Availability: Liquid cultures may not be as widely available as freeze-dried cultures.

Fresh Cultures

Fresh cultures, also sometimes called “mother cultures,” are living cultures that are actively fermenting. These are typically maintained by the user and passed down over time. Examples include sourdough starters, kombucha scobys, and kefir grains.Fresh cultures require regular feeding and maintenance to keep them active and healthy. They offer a connection to a specific lineage of microorganisms, but they also require more care and attention.The advantages of fresh cultures include:

- Unique Flavor Profiles: Over time, fresh cultures can develop unique and complex flavor profiles.

- Cost-Effective: Once established, they are a continuous source of culture, eliminating the need to purchase new cultures.

- Community: Sharing and exchanging fresh cultures can create a sense of community among fermenters.

The disadvantages of fresh cultures include:

- High Maintenance: They require regular feeding and care.

- Potential for Contamination: They are susceptible to contamination if not properly maintained.

- Time Commitment: Maintaining a fresh culture requires a significant time commitment.

Purchasing Starter Cultures

When purchasing starter cultures, consider the following factors:

- Source: Choose a reputable supplier that specializes in starter cultures and fermentation supplies. Look for companies with a good reputation and positive customer reviews.

- Culture Type: Ensure the culture is appropriate for the food you plan to ferment. Consider whether you need a culture for yogurt, cheese, sourdough, or other products.

- Form: Decide which form of culture best suits your needs, considering shelf life, convenience, and storage requirements.

- Ingredients: Check the ingredient list to ensure the culture is free from any additives or ingredients you want to avoid.

- Quantity: Determine the appropriate quantity based on your intended use. Starter cultures are often sold in small packets or vials, and the amount needed depends on the batch size.

- Storage Instructions: Follow the supplier’s storage instructions carefully to maintain the viability of the culture. Freeze-dried cultures should generally be stored in the freezer, while liquid cultures may require refrigeration.

- Expiration Date: Check the expiration date to ensure the culture is fresh and viable.

- Price: Compare prices from different suppliers to find the best value.

- Reviews and Recommendations: Read reviews and seek recommendations from experienced fermenters to help you choose a reliable supplier and culture.

Examples of reputable suppliers include: Cultures for Health, New England Cheesemaking Supply Company, and Breadtopia. These suppliers offer a variety of starter cultures, equipment, and resources for home fermentation.

Selecting the Right Starter Culture

Choosing the perfect starter culture is crucial for successful fermentation. The right culture unlocks desired flavors, textures, and shelf life, making your homemade creations a delicious reality. This section provides a detailed guide to help you navigate the selection process with confidence.

Factors to Consider When Choosing a Starter Culture

Several factors influence the choice of starter culture. Considering these elements will help you achieve your desired results and avoid unwanted outcomes.

- Intended Food: The type of food you plan to ferment is the primary determinant. Different cultures are designed for specific foods. For example, a yogurt culture won’t work for making sourdough bread, and vice versa. The food’s composition (e.g., milk type, grain type) will also impact the culture’s performance.

- Desired Flavor Profile: Starter cultures offer a wide range of flavor profiles. Some produce a tangy, sharp taste, while others create a milder, creamier flavor. Researching the flavor characteristics of different cultures will help you select one that aligns with your taste preferences. Consider that flavor development is also affected by factors like fermentation time and temperature.

- Desired Texture: Texture is another key consideration. Some cultures result in thick, creamy products, while others yield a thinner consistency. The desired texture can be achieved by selecting the appropriate culture and adjusting fermentation parameters like temperature and the presence of stabilizers.

- Shelf Life: The shelf life of the final product is significantly influenced by the starter culture used. Some cultures produce compounds that naturally extend shelf life, while others might result in a shorter preservation period. The culture’s ability to inhibit spoilage organisms is a key factor in determining shelf life.

- Ease of Use: Consider your experience level and the complexity of the culture. Some cultures are easier to use than others, requiring less precise temperature control or incubation times. Starter cultures that are more complex might require more attention to detail.

Understanding Culture Packaging Information

Reading and understanding the information on culture packaging is essential for successful fermentation. The packaging provides critical information about the culture’s characteristics and usage.

- Culture Type: The packaging will clearly indicate the type of culture (e.g., yogurt, kefir, sourdough, cheese).

- Strain(s) of Bacteria/Cultures Used: The specific strains of bacteria or other microorganisms used in the culture are usually listed. This information helps you understand the culture’s characteristics and potential flavor profiles.

- Instructions for Use: The packaging will provide detailed instructions on how to use the culture, including the recommended amount, temperature, and incubation time.

- Storage Instructions: Proper storage is essential to maintain the culture’s viability. The packaging will specify the ideal storage conditions, typically refrigeration or freezing.

- Expiration Date: Starter cultures have a limited shelf life. The expiration date indicates when the culture is no longer guaranteed to be viable.

- Ingredients: The ingredient list specifies any additional ingredients, such as milk powder or stabilizers, which may be included.

- Allergen Information: Packages often highlight potential allergens present in the culture.

Comparative Table: Yogurt Starter Cultures

The following table compares different yogurt starter cultures, highlighting their flavor, texture, and expected results. This table offers a quick reference guide to aid in your selection process.

| Culture Type | Flavor Profile | Texture | Expected Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Yogurt Culture (Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus) | Tangy, slightly acidic | Thick, creamy | Classic yogurt flavor, often with a slightly tart taste. Produces a thick, spoonable texture. |

| Mild Yogurt Culture (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium spp.) | Milder, less tangy | Thicker, can be creamy | Creamier flavor profile, less acidic. May have added probiotic benefits. |

| Greek Yogurt Culture (Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, plus straining) | Tangy, concentrated flavor | Very thick, dense | Produces a very thick, dense yogurt. The flavor is more concentrated due to the removal of whey during straining. |

| Kefir Culture (Lactobacillus spp., Lactococcus spp., Leuconostoc spp., Acetobacter spp., and yeasts) | Tangy, slightly effervescent | Thin, drinkable, or can be thickened | Produces a thinner, more drinkable yogurt. Often has a slightly effervescent quality and a complex flavor profile due to the variety of microorganisms. |

Preparing and Activating Starter Cultures

Getting your starter culture ready is a crucial step in ensuring successful fermentation. Whether you’re working with freeze-dried packets or a liquid culture, proper activation and maintenance are key to cultivating a thriving colony of beneficial microorganisms. This section will guide you through the process, providing you with the knowledge to prepare, propagate, and maintain your starter cultures for delicious and healthy results.

Activating Freeze-Dried Starter Cultures

Freeze-dried cultures are dormant and need to be rehydrated and activated before use. The process generally involves rehydrating the culture in a suitable medium, such as milk or water, and allowing it to incubate under specific temperature conditions.

- Rehydration: Carefully follow the manufacturer’s instructions, as these may vary slightly depending on the specific culture. Typically, this involves adding the freeze-dried powder to a specific amount of sterilized liquid. For example, a yogurt culture might be added to pasteurized milk.

- Incubation: The rehydrated culture needs time to wake up and multiply. This usually involves incubating the mixture at a specific temperature for a set duration. For instance, yogurt cultures often require incubation at around 40-45°C (104-113°F) for several hours, until the desired consistency and acidity are achieved. A yogurt maker or a warm environment is often used to maintain the correct temperature.

- Monitoring: During incubation, it’s essential to monitor the culture for signs of activity, such as thickening, changes in aroma, or the development of acidity. Tasting the product can also indicate when it’s ready.

- Storage: Once activated, the starter culture is ready for use in your recipes. If you plan to use it immediately, you can add it to your ingredients. If you want to store it for later use, refrigerate it to slow down the fermentation process.

Propagating Liquid Starter Cultures

Liquid starter cultures, also known as mother cultures, are alive and active. They can be used directly for fermentation or propagated to create more culture. This propagation process, essentially, involves feeding the existing culture and providing it with the conditions it needs to multiply.

- Feeding: Liquid cultures need regular feeding with fresh ingredients. For example, a sourdough starter needs to be fed with flour and water. The ratio of starter to fresh ingredients will depend on the specific culture and your desired fermentation speed. A common ratio is 1:1:1 (starter:flour:water).

- Incubation: Like freeze-dried cultures, liquid cultures require a suitable environment for growth. This typically involves maintaining a specific temperature. For example, a sourdough starter often thrives at room temperature, but warmer temperatures can speed up the fermentation process.

- Observation: Monitoring the culture for signs of activity is crucial. This includes observing bubbles, changes in volume, and changes in aroma. A rising and falling starter is a good indicator of activity.

- Dividing: Once the culture has reached its peak activity, you can divide it into portions for future use. Discarding or using a portion of the culture helps maintain its health and prevents it from becoming too acidic.

- Storage: When not actively using a liquid culture, store it in the refrigerator to slow down its activity and extend its life. Remember to feed it regularly, even when refrigerated, to keep it healthy.

Maintaining a Healthy Starter Culture

Maintaining a healthy starter culture is a continuous process that involves providing the right environment, regular feeding, and careful observation. Proper maintenance ensures that your culture remains active, flavorful, and safe for consumption.

- Regular Feeding: Regularly feeding the culture is the most important aspect of maintenance. This provides the microorganisms with the nutrients they need to survive and multiply. The frequency of feeding depends on the type of culture and the storage conditions. For example, a sourdough starter stored at room temperature may need to be fed daily, while one stored in the refrigerator can be fed weekly.

- Proper Storage: Storing the culture correctly helps control its activity and prevent spoilage. Refrigeration slows down the fermentation process and extends the life of the culture. Always use clean containers and lids to prevent contamination.

- Temperature Control: Maintaining the appropriate temperature is crucial for the culture’s activity. Too high or too low temperatures can inhibit growth. For example, yogurt cultures need a warm environment, while kefir cultures prefer room temperature.

- Observation and Monitoring: Regularly observe the culture for signs of activity and any changes in appearance or smell. A healthy culture will typically exhibit consistent bubbling, a pleasant aroma, and a predictable rate of fermentation. Any unusual changes, such as mold growth or an off-putting smell, could indicate a problem.

- Sanitation: Maintaining a clean environment is vital to prevent contamination. Always use clean utensils and containers when handling the culture. Avoid introducing foreign substances into the culture.

- Discarding Excess: When feeding liquid cultures, you’ll typically have more culture than you need. Regularly discarding a portion of the culture prevents it from becoming overly acidic and helps maintain a balanced ecosystem.

Using Starter Cultures in Food Production

Starter cultures are the workhorses of fermented food production, transforming raw ingredients into delicious and often shelf-stable products. Their application varies depending on the desired food, but the fundamental principles of harnessing microbial activity remain constant. This section details the practical aspects of using starter cultures, focusing on the steps involved and the critical factors that influence successful fermentation.

General Steps in Using Starter Cultures

The process of using a starter culture typically involves several key steps. These steps are crucial for ensuring the culture thrives and effectively transforms the food.The general steps include:

- Preparation of the Base Ingredient: This involves preparing the food base, which could be milk for yogurt, grains for sourdough, or vegetables for sauerkraut. This preparation often includes cleaning, chopping, or cooking the ingredient.

- Inoculation with the Starter Culture: The starter culture is introduced to the prepared base. This could be a direct addition of a freeze-dried culture or the use of a previously prepared culture, such as a sourdough starter.

- Incubation: The inoculated mixture is kept under specific conditions, primarily temperature, for a set duration. This environment allows the starter culture to multiply and perform its fermentation activity.

- Monitoring: Regular observation of the fermentation process is important. This includes checking for changes in texture, smell, and taste, as these indicate the progress of the fermentation.

- Termination of Fermentation: Fermentation is stopped when the desired characteristics are achieved. This might involve chilling the product to slow down microbial activity or cooking it to kill the microbes.

- Storage: The final product is stored appropriately to maintain its quality and prevent spoilage. This could be in the refrigerator, freezer, or a cool, dry place, depending on the food type.

Controlling Fermentation Conditions

Controlling fermentation conditions is critical for achieving the desired results. Temperature, humidity, and time are the most significant factors that influence the activity of the starter culture.

- Temperature: Temperature is the most critical factor. Different cultures have different optimal temperature ranges. For example, yogurt cultures typically thrive at 40-45°C (104-113°F), while sourdough starters prefer cooler temperatures, around 20-25°C (68-77°F). Maintaining the correct temperature ensures that the desired microbes dominate the fermentation process.

- Humidity: Humidity plays a role in preventing the food from drying out, particularly in the case of fermented vegetables. Ensuring adequate humidity can be achieved by covering the fermenting food or using a fermentation crock with an airlock.

- Time: The duration of fermentation influences the final product’s flavor, texture, and acidity. Longer fermentation times typically result in more complex flavors and higher acidity. However, over-fermentation can lead to undesirable results. The optimal fermentation time varies depending on the food and the specific culture used.

Making Sourdough Bread: A Step-by-Step Guide

Sourdough bread is a classic example of food produced using a starter culture. The process is a combination of patience, understanding, and attention to detail.Here’s a detailed guide:

- Maintaining the Sourdough Starter:

- Feed your sourdough starter regularly, usually once or twice a day, with equal parts of flour and water (e.g., 100g flour + 100g water). This keeps the culture active and ensures a robust rise.

- Discard a portion of the starter before feeding to prevent the culture from becoming too large.

- Observe the starter for signs of activity, such as bubbles and a doubling in size, indicating it is ready for use.

- Mixing the Dough:

- Combine the starter (typically around 100-200g), flour (e.g., 500g), and water (e.g., 350g) in a bowl.

- Mix until a shaggy dough forms. Let it rest (autolyse) for 30-60 minutes. This allows the flour to fully hydrate.

- Adding Salt and Initial Kneading:

- Add salt (e.g., 10g) to the dough.

- Knead the dough for a few minutes until the salt is incorporated.

- Bulk Fermentation (First Rise):

- Allow the dough to rise in a lightly oiled bowl, covered, for 4-6 hours at room temperature (around 21-24°C/70-75°F).

- During bulk fermentation, perform “stretch and folds” every 30-60 minutes for the first 2-3 hours. This strengthens the gluten structure. To do this, gently stretch a portion of the dough upwards and fold it over onto itself. Rotate the bowl and repeat.

- Shaping the Loaf:

- Gently shape the dough into a round (boule) or an oblong (batard).

- Place the shaped dough in a banneton basket (a proofing basket) lined with flour or a floured cloth.

- Proofing (Second Rise):

- Refrigerate the shaped dough for 12-24 hours. This slow, cold proofing develops flavor and improves the crust.

- Baking:

- Preheat the oven to 230°C (450°F) with a Dutch oven inside.

- Carefully remove the hot Dutch oven. Place the dough inside, score the top with a knife or lame (a small blade), and cover with the lid.

- Bake covered for 20 minutes.

- Remove the lid and bake for another 25-30 minutes, or until the crust is deeply golden brown.

- Cooling:

- Let the bread cool completely on a wire rack before slicing and enjoying. This is crucial for allowing the internal structure to set.

Important Note: The timings mentioned in this guide are approximate and can vary based on environmental conditions and the activity of the starter. Adjust accordingly.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Fermenting food is a fascinating process, but sometimes things don’t go as planned. Understanding and addressing common fermentation problems is key to successful and delicious results. This section will guide you through identifying, diagnosing, and resolving issues that may arise during the fermentation process.

Slow Fermentation

Slow fermentation can be frustrating, but it’s often a manageable problem. This can manifest as a longer-than-expected fermentation time, or a lack of visible activity, such as bubbling or changes in texture. Several factors can contribute to slow fermentation.

- Inactive or Weak Starter Culture: The most common cause. If your starter culture isn’t viable or is weak, it won’t ferment your food efficiently.

- Possible Cause: The starter culture may be old, improperly stored, or exposed to extreme temperatures. It could also have been contaminated.

- Solution:

- Use a fresh, active starter culture.

- Ensure your starter culture is stored correctly, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Rehydrate or reactivate your starter culture according to the instructions provided.

- If using a homemade starter, feed it regularly and observe for signs of activity (bubbling, sour smell).

- Low Temperature: Fermentation is temperature-dependent. Colder temperatures slow down microbial activity.

- Possible Cause: The fermentation environment is too cold for the specific starter culture and the food being fermented.

- Solution:

- Increase the ambient temperature. Use a warmer, a heating pad, or a fermentation chamber to maintain the optimal temperature range recommended for your specific starter culture.

- Monitor the temperature regularly with a thermometer.

- Insufficient Food for the Microbes: The microbes need a food source (sugars, starches) to ferment.

- Possible Cause: The food lacks sufficient carbohydrates, or the carbohydrates are not readily available.

- Solution:

- Ensure the food contains enough sugar or starch for the specific fermentation process.

- If necessary, add a small amount of sugar (e.g., honey, maple syrup, or a small amount of white sugar) to provide additional food for the microbes. Be cautious not to add too much, as this can negatively affect the final product’s flavor.

- For some fermentations, adding a small amount of unrefined, high-quality flour (like rye or whole wheat) can boost fermentation activity.

- Presence of Inhibitors: Certain substances can inhibit microbial activity.

- Possible Cause: The presence of excessive salt, chlorine in the water, or other antimicrobial agents.

- Solution:

- Use filtered water to remove chlorine.

- Ensure the salt concentration is within the recommended range for the specific fermentation process.

- Avoid using metal utensils or containers that could leach into the food and inhibit fermentation.

Off-Flavors

Undesirable flavors can develop during fermentation, often indicating an imbalance in the microbial community or the presence of undesirable microorganisms. The type of off-flavor can help identify the cause.

- Sourness: Excessive sourness is a common problem, particularly in long fermentations.

- Possible Cause: Over-fermentation, or the presence of too much lactic acid production.

- Solution:

- Reduce the fermentation time.

- Lower the fermentation temperature to slow down the process.

- Use a smaller amount of starter culture.

- Bitterness: Bitterness can arise in certain fermented foods.

- Possible Cause: The breakdown of certain compounds during fermentation, or the presence of specific strains of microorganisms.

- Solution:

- Experiment with different starter cultures.

- Adjust the recipe to include ingredients that can counteract bitterness, like a small amount of sweetness.

- Carefully monitor the fermentation process to prevent over-fermentation.

- Rancid or Putrid Flavors: These flavors are highly undesirable.

- Possible Cause: Contamination with spoilage organisms, or improper storage conditions.

- Solution:

- Discard the batch of fermented food.

- Ensure all equipment and utensils are thoroughly sanitized.

- Use fresh, high-quality ingredients.

- Maintain proper storage conditions (temperature, humidity) after fermentation.

- Yeasty or Alcoholic Flavors: This may indicate the presence of yeasts and is more common in certain fermentations.

- Possible Cause: Uncontrolled fermentation, or the activity of wild yeasts.

- Solution:

- Ensure you are using the correct starter culture.

- Control the fermentation environment to prevent the growth of wild yeasts.

- Consider adjusting the recipe to reduce the sugar content.

Mold or Surface Growth

The appearance of mold or unwanted surface growth is a sign of contamination. It’s crucial to identify the type of growth and determine whether the food is safe.

- Mold: Mold is a visible, fuzzy growth that can be white, green, black, or other colors.

- Possible Cause: Exposure to airborne mold spores, or improper storage conditions.

- Solution:

- Discard the entire batch of fermented food if mold is present.

- Sanitize all equipment and utensils thoroughly.

- Ensure the fermentation environment is clean and well-ventilated.

- Maintain proper storage conditions to prevent mold growth.

- Kahm Yeast: A harmless but undesirable white, often wrinkly film on the surface.

- Possible Cause: Exposure to air and/or too much humidity.

- Solution:

- The Kahm yeast can often be skimmed off the surface.

- Improve air circulation and ventilation.

- Store the fermented food in a cooler, drier environment.

Texture Problems

Texture changes can affect the final product’s quality.

- Slime: A slimy texture is usually an indication of bacterial contamination.

- Possible Cause: Growth of undesirable bacteria.

- Solution:

- Discard the batch of fermented food.

- Thoroughly sanitize all equipment and utensils.

- Use fresh, high-quality ingredients.

- Softness or Mushiness: Can be a sign of over-fermentation, or bacterial activity.

- Possible Cause: Over-fermentation, or the activity of undesirable bacteria.

- Solution:

- Reduce the fermentation time.

- Adjust the fermentation temperature.

- Use a smaller amount of starter culture.

Storing Starter Cultures

Proper storage is crucial for preserving the viability and activity of your starter cultures. Think of these tiny microorganisms as living beings; they need the right environment to survive and thrive. Incorrect storage can lead to a decline in their numbers, reduced fermentation activity, and ultimately, less successful food production. This section will guide you through the best practices for storing your precious cultures.

Refrigeration of Starter Cultures

Refrigeration is the most common method for short-term storage of many starter cultures. It slows down the metabolic activity of the microorganisms, putting them in a state of dormancy and extending their lifespan.

- Types of Cultures: Refrigeration is generally suitable for liquid and freeze-dried cultures that have been rehydrated. It’s also a good option for fresh, active cultures, such as those used in yogurt or sourdough.

- Temperature: Maintain a consistent refrigerator temperature between 35-40°F (2-4°C). Avoid fluctuating temperatures, as these can stress the cultures.

- Containers: Store cultures in clean, airtight containers to prevent contamination and maintain moisture levels. Glass jars or food-grade plastic containers work well.

- Shelf Life: Refrigerated cultures can typically be stored for several weeks, or even months, depending on the specific culture and its initial condition. Always check for signs of spoilage, such as mold growth or unusual odors, before use. For example, a sourdough starter can last for a week or two in the fridge, and needs to be fed regularly.

Freezing of Starter Cultures

Freezing offers a longer-term storage solution, especially for cultures you don’t plan to use frequently. The freezing process effectively halts microbial activity, allowing you to preserve cultures for extended periods.

- Types of Cultures: Freezing is most effective for freeze-dried cultures and actively growing cultures. However, not all cultures tolerate freezing equally well. Some cultures, particularly those in liquid form, may experience a reduction in viability after freezing and thawing.

- Preparation: Before freezing, make sure your cultures are properly prepared. For liquid cultures, you might consider adding a cryoprotectant, such as a small amount of milk powder or skim milk, to help protect the cells from damage during freezing.

- Freezing Process: Freeze cultures quickly to minimize ice crystal formation, which can damage the cells. Use freezer-safe containers, such as small, airtight plastic bags or freezer-safe containers. Label each container with the culture type, date, and any relevant information.

- Temperature: Store cultures at a constant freezer temperature of 0°F (-18°C) or lower.

- Thawing: Thaw frozen cultures slowly in the refrigerator before use. Avoid rapid thawing at room temperature, as this can shock the microorganisms and reduce their viability. Once thawed, use the culture as soon as possible.

- Shelf Life: Frozen cultures can be stored for several months, or even years, depending on the culture and storage conditions. However, the longer a culture is frozen, the more its viability may decline.

Best Practices for Long-Term Storage

- Choose the Right Method: Select the appropriate storage method (refrigeration or freezing) based on the culture type and your intended usage.

- Maintain Optimal Temperatures: Keep refrigeration temperatures consistently between 35-40°F (2-4°C) and freezing temperatures at 0°F (-18°C) or lower.

- Use Airtight Containers: Store cultures in clean, airtight containers to prevent contamination and maintain moisture.

- Label Clearly: Label all containers with the culture type, date of preparation or freezing, and any relevant information.

- Monitor for Spoilage: Regularly inspect cultures for signs of spoilage, such as mold, off-odors, or changes in appearance. Discard any cultures that show signs of spoilage.

- Consider a Backup: If you rely on a particular culture, consider creating a backup culture to ensure you always have a viable source.

Safety Considerations

Working with starter cultures is generally safe, but it’s crucial to prioritize food safety to prevent the growth of unwanted microorganisms that could lead to spoilage or illness. Implementing proper safety measures ensures the production of safe and high-quality fermented foods. Understanding and following these guidelines is essential for a successful and safe fermentation process.

Food Safety Precautions

To minimize the risk of contamination and ensure food safety, several precautions should be observed throughout the fermentation process.

- Hand Hygiene: Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water before handling any ingredients or equipment. This is the first and most important step in preventing contamination.

- Clean Equipment: Sanitize all equipment, including utensils, jars, and containers, with hot, soapy water and then either boiling water or a food-grade sanitizer. This removes any existing microorganisms.

- Ingredient Sourcing: Use fresh, high-quality ingredients. Avoid ingredients that show signs of spoilage or damage.

- Proper Temperatures: Maintain the recommended temperatures for each specific culture and fermentation process. Temperature control is crucial for the growth of the desired microorganisms and to inhibit the growth of undesirable ones.

- Acidification: Ensure proper acidification, which is key to inhibiting the growth of harmful bacteria. This is often achieved through the production of lactic acid by the starter culture.

- Monitor for Signs of Spoilage: Regularly inspect your fermentations for any unusual changes in appearance, smell, or texture.

- Proper Storage: Store finished products correctly to maintain their quality and safety.

Identifying Signs of Contamination

Recognizing signs of contamination is vital to prevent the consumption of unsafe fermented foods. The following indicators can help identify potential problems.

- Unusual Odors: A sour, putrid, or otherwise unpleasant smell indicates spoilage. The expected aroma depends on the specific fermentation, but any significant deviation is a warning sign. For example, the putrid smell of rotten eggs, usually indicates the presence of sulfur-producing bacteria.

- Off-Color Appearance: Discoloration, such as mold growth, a change in the color of the liquid, or the presence of any unusual colors, can indicate contamination. For example, green or black spots in cheese or the development of a strange color on the surface of a ferment.

- Mold or Surface Growth: The presence of mold or any unwanted surface growth is a clear sign of contamination. This includes fuzzy, colored growths.

- Unusual Textures: Changes in texture, such as sliminess, excessive gas production, or a change from the expected consistency, may indicate spoilage. For instance, excessive gas production in a jar of sauerkraut can lead to a bulging lid, a sign of spoilage.

- Off-Taste: A bitter, metallic, or otherwise unpleasant taste is a sign that the product is not safe to consume.

Maintaining a Clean and Sterile Work Environment

A clean and sterile work environment is crucial for preventing contamination. Implement the following practices.

- Dedicated Workspace: Designate a specific area for fermentation and food preparation.

- Surface Cleaning: Clean and sanitize all surfaces before and after each use.

- Equipment Sterilization: Sterilize all equipment, including jars, utensils, and any other items that will come into contact with the ingredients.

- Air Quality: Minimize air exposure to reduce the chance of airborne contaminants.

- Proper Waste Disposal: Dispose of any spoiled products or contaminated materials properly to prevent cross-contamination.

- Regular Inspections: Regularly inspect your equipment and work area for any signs of mold or bacterial growth.

Outcome Summary

In conclusion, “How to Choose and Use the Right Starter Cultures” offers a comprehensive roadmap for your fermentation journey. From selecting the ideal culture to troubleshooting common issues, you now have the tools to create a world of delicious, homemade fermented foods. Embrace the power of these tiny organisms, and unlock a new realm of culinary creativity, taste, and well-being.

Happy fermenting!